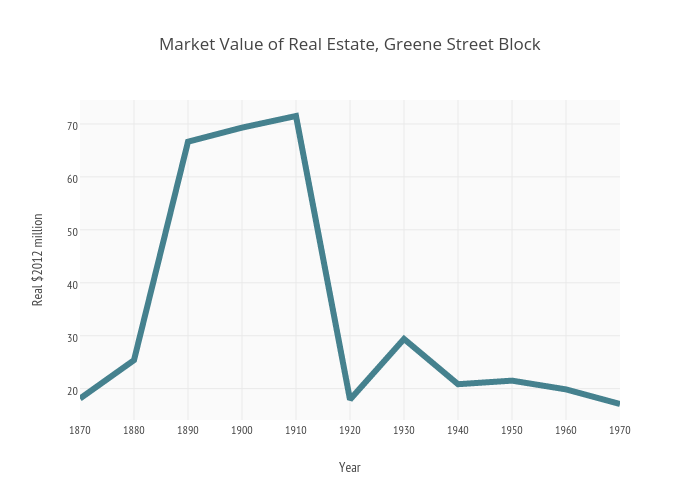

The fall of Greene Street?

A squatter’s village, or “Packing Box City,” sprouted up in the 1930’s at Houston Street, like in many cities after the Great Depression.

Sperr, Percy Loomis. "Squatters Colony on Houston Street," 1933. New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Sperr, Percy Loomis. "Squatters Colony on Houston Street," 1933. New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Holden-McLaughlin Plan, 1945. Found in Schwartz, Joel. The New York Approach: Robert Moses, Urban Liberals, and Redevelopment of the Inner City. Ohio State University Press: 1993, 148.

Lower Manhattan Expressway

Clips from Arteries of New York, Encyclopedia Britannica Films, 1941. Public domain footage, found on Internet Archive.

LOMEX model, by architect Paul Rudolph. Library of Congress.

I take this occasion to plead for the courageous, clean-cut, surgical removal of all our old slums.... [T]here can be no real neighborhood reconstruction, no superblocks, no reduction of ground coverage, no widening of boundary streets, no playgrounds, no new schools, without the unflinching surgery which cuts out the whole cancer and leaves no part of it which can grow again, and spread and perpetuate old miseries.

- Robert Moses

- Robert Moses

Map by architect Paul Rudolph. Library of Congress.

The blocks surrounding Greene Street may have looked like this...

Rendering of streetscape, LOMEX. Paul Rudolph, 1967. Library of Congress.

The Moses plan mobilized neighborhood resistance.

The Joint Emergency Committee to Close Washington Square Park to Traffic -- derided by Moses as “a bunch of mothers” -- successfully fought for a ban of automobile traffic through Washington Square Park.

Neighborhood activists then formed The Joint Committee to Stop the Lower Manhattan Expressway. The group included Jane Jacobs, the urban activist who gained national attention for her advocacy of mixed-use spaces, high-density neighborhoods, and bottom-up community planning in her book The Death and Life of American Cities in 1961.

Jane Jacobs in Washington Square Park, 1963. Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images, found in Tablet magazine.

Clips from "Village Sunday, 1960." Public domain, found at Internet Archive

...[T]hat the sight of people attracts still other people, is something that city planners and city architectural designers seem to find incomprehensible. They operate on the premise that city people seek the sight of emptiness, obvious order and quiet. Nothing could be less true. The presences of great numbers of people gathered together in cities should not only be frankly accepted as a physical fact – they should also be enjoyed as an asset and their presence celebrated...As in the pseudoscience of bloodletting, just so in the pseudoscience of city rebuilding and planning, years of learning and a plethora of subtle and complicated dogma have arisen on a foundation of nonsense.

- Jane Jacobs

- Jane Jacobs

In this case, the local resistance won the argument. Robert Moses lost his post in 1968, and in 1969 the LOMEX plan was definitively dead. The Greene Street block survived with its previous building stock untouched.

Jane Jacobs at press conference, 1961. Stanziola, Phil. Library of Congress

Neighborhood activists won against big city planners.